Yesterday the Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron brought the curtain down on the annual political road show which is party conference season. Party conferences are often pretty stale affairs. Each political leader endeavours to reconnect with his tribal supporters. Policy promises are made (and usually junked shortly afterwards), competing parties are lampooned and almost every politician who takes to the podium for their set piece speech enjoys 15 minutes of ‘conference fame’ before their insightful pronouncements or carefully crafted jokes are consigned to the dustbin, as the media searches for the next sound bite (or preferably gaff). But this year’s been a little different.

Yesterday the Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron brought the curtain down on the annual political road show which is party conference season. Party conferences are often pretty stale affairs. Each political leader endeavours to reconnect with his tribal supporters. Policy promises are made (and usually junked shortly afterwards), competing parties are lampooned and almost every politician who takes to the podium for their set piece speech enjoys 15 minutes of ‘conference fame’ before their insightful pronouncements or carefully crafted jokes are consigned to the dustbin, as the media searches for the next sound bite (or preferably gaff). But this year’s been a little different.

All three of the main political party leaders will return to parliament on Monday feeling the wind in their sails and the hope that they’re on the road to securing that crucial ‘cut through’ with the British electorate which will catapult each of them into government after the 2015 general election.

Okay, maybe that’s a little overly optimistic.

The leader of the Liberal Democrats and Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg may have had a ‘good conference’ but he knows there’s no chance of his party usurping either Labour or the Conservatives and becoming the major party in Westminster. But he played to his strengths. His appeal to his own party is confused at best, although what he’s given them is a taste of power and they love it. If the Lib Dems spent the last three years getting used to being in government after more than ninety years in opposition, it’s now become a drug and they want more of it.

The leader of the Liberal Democrats and Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg may have had a ‘good conference’ but he knows there’s no chance of his party usurping either Labour or the Conservatives and becoming the major party in Westminster. But he played to his strengths. His appeal to his own party is confused at best, although what he’s given them is a taste of power and they love it. If the Lib Dems spent the last three years getting used to being in government after more than ninety years in opposition, it’s now become a drug and they want more of it.

Bereft of almost any new policy announcements the Liberal Democrat leader’s overriding message was don’t let the Conservatives steal all the credit for the economic upturn. Mr Clegg claimed that only the Lib Dems can act as handbrake on the Conservatives or Labour in government. Much to the British public’s surprise coalition government has worked and it’s all down to the Lib Dems.

Opinion remains divided on the accuracy of this claim. The Lib Dems are routinely in fourth place in the polls (trailing Ukip, the growing right wing party that’s sucking voters away from the Conservatives) and there’s little chance of a shift in the run up to the election. Where previously they had always enjoyed being the repository of protest votes they now have a record in government to defend and they have their detractors.

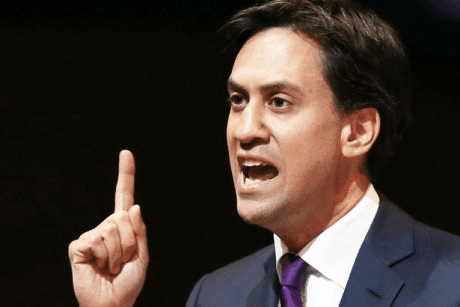

If Mr Clegg set out his party’s credentials for continuing in government, the Labour leader Ed Miliband’s conference speech was a ‘tour de force’ sending shock waves across the political landscape. Often maligned as much by his own party as by the others, Mr Miliband threw down the gauntlet and staked his leadership on tackling Britain’s ‘cost of living crisis’.

He accused David Cameron of presiding over a recovery that only benefited the richest few. Unlike the Prime Minister he was prepared to stand up to vested interests of big business. The Labour leader saved his main salvo for the energy companies, claiming if elected in 2015 he would abolish the existing energy regulator and freeze gas and electricity bills for every home and business in the country for twenty months.

He accused David Cameron of presiding over a recovery that only benefited the richest few. Unlike the Prime Minister he was prepared to stand up to vested interests of big business. The Labour leader saved his main salvo for the energy companies, claiming if elected in 2015 he would abolish the existing energy regulator and freeze gas and electricity bills for every home and business in the country for twenty months.

Unsurprisingly the reaction from the UK business community was apoplectic. Stock prices of the ‘big six’ energy companies nosedived. And the business lobby went on the offensive, dismissing Mr Miliband’s announcement as a throwback to the 1970s when Britain lurched to the left under consecutive Labour governments. But this time around the Labour leader has struck a chord with public sentiment. Wages have remained stagnant since the crash but energy and food prices continue to soar.

The fledgling economic recovery has forced Labour to abandon its criticism of the coalition’s strategy to reduce the deficit, and shift its sights to a recovery that benefits ordinary people, not just the privileged few. Mr Miliband’s repeated sound bite that ‘Britain can do better than this’ will become Labour’s election campaign slogan.

There’s little doubt that Labour delegates left conference with a warm fuzzy feeling in their stomachs. Their leader had pitched his unreservedly Labour stake in the ground, and while reinforcing the core vote, there will be concerns whether he can appeal to those voters in ‘Middle England’ who are essential to win over if Labour is to secure a comfortable majority government at the next election. However the fact remains that Labour enjoys a consistent 10% lead in the polls and only requires a 1% swing to secure a majority. Mr Miliband remains in pole position.

Last but by no means least the Conservative leader David Cameron responded to the challenges thrown down by his adversaries. For Mr Cameron the recovery job is only half completed. There was no fanfare or jubilation. The conference slogan was the party ‘For hard working people’ and the Prime Minister rammed home again and again that unlike Mr Miliband he supported business, welfare reform and a reduction in taxes. Short on policy rhetoric he capitalised on the role of statesman to point to his vision of Britain as a country that ‘can stand tall again, home and abroad’.

By virtually ignoring the Liberal Democrats and establishing clear dividing lines between the Conservatives and Labour, Mr Cameron believes his ‘recovery for all’ can best deliver results for the country over Labour’s more interventionist strategy.

In essence, yesterday marked the beginning of the phoney election campaign. But unlike with previous leaders and elections, the policy choices on offer could be starker than they have been for a generation, and just how much people personally feel that recovery will determine whether Mr Cameron’s time in office is up or not.